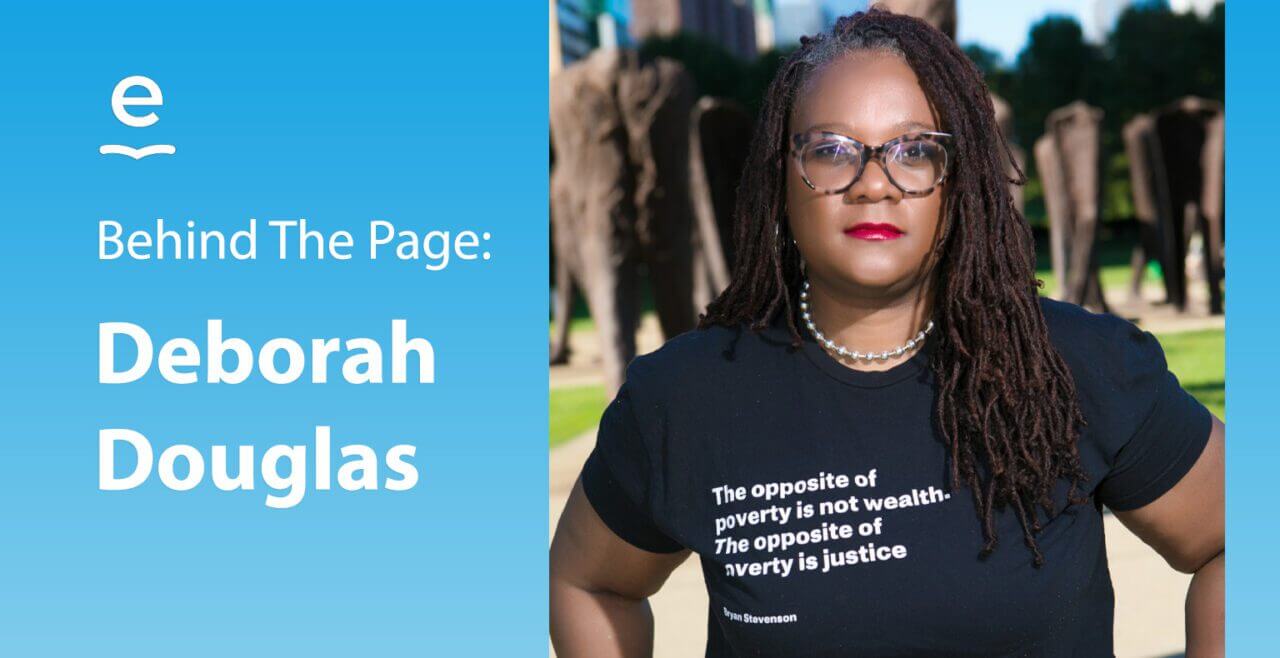

Born in Chicago’s West Side and raised in Detroit and outside Memphis, Deborah Douglas, the Eugene S. Pulliam Distinguished Visiting Professor of Journalism at DePauw University and author of the first travel guide to the new U.S. Civil Rights Trail, describes herself as a Great Migration baby.

“I started learning in a revolutionary atmosphere,” she said. “I didn’t know anything about the uprising, but I did know as a five-year-old that something had gone on. There was something different about where I was––there was this kind of energy in the air. I felt like I needed to catch it and do something with it.”

That revolutionary energy continues to drive Douglas’ work. As an award-winning journalist, author and thought leader, Douglas works to reshape the dehumanizing narratives that surround marginalized communities––particularly Black communities––in the American cultural conversation.

“I guess I accepted journalistic orthodoxy for much of my career, that there was a way to do things and it was the way to do things, and I was not to interrogate it, but I was supposed to implement the rules,” Douglas said. “And now all I do all day long is interrogate the rules and advocate for breaking rules that I don’t think make sense anymore.”

Take the journalistic ideal of approaching a story with “objectivity.” While many treat this as gospel, Douglas and others question the feasibility of this dogma when our internalized biases touch every part of the writing process––from the pitch to the interviews to the final edits, reporters are inevitably informed by their background and assumptions.

This explains why media organizations often “deficit-frame” rather than “asset-frame” marginalized groups in their coverage, Douglas said, applying to the media industry a concept created by social entrepreneur Trabian Shorters to describe non-profit work. “Deficit-framing is when you define people by the worst thing that’s ever happened to them,” she said. Asset-framing, in contrast, depicts people as more than just their problems and treats them as experts on their own experiences.

“I think that a lot of the way we’ve approached journalism for eons is that we center established power and their concerns, and we don’t center everyday people. And then we wonder where our audiences have gone when we’ve spent years ignoring them or ignoring the nuances of their lives,” Douglas said.

Douglas described another egregious gap in news coverage that seeps into everyday life––she is credited with coining the term “depresence,” defined as “a pathological failure to regard the humanity of Black women in places and narratives as if they were not even there” in her social media post.

When she covered the campaign to take down Confederate monuments in Memphis public parks, Douglas noted how the coverage downplayed the importance of the movement’s leader, Tami Sawyer, a Black woman.

“She was depresenced in those spaces by the powers that be, and also she was depresenced in the narratives,” Douglas said. “When they talked about it, they left out details and specificity that really acknowledged her leadership and her power in that space.”

It reminded her of depresencing in her own life––as a journalist, she can recall many occasions in which she addressed a white man with a particular question, and he looked right past her. It’s another glaring example of the very real social impacts of flawed storytelling. Douglas is hoping to use her platform at DePauw to spread awareness of the phenomenon and to validate the experiences of other Black women.

Douglas’ new book––“U.S. Civil Rights Trail: A Traveler’s Guide to the People, Places and Events that Made the Movement”––is an exciting antidote to these desolate narratives. It’s the first and only book to traverse this new U.S. Civil Rights Trail, officially designated in 2018 by Travel South, mapping civil rights activism in the South and its lasting impact.

Douglas argues that there’s power in making this history tangible through travel. In every chapter, she weaves between past and present, curating crucial sights of civil rights history, tours by local guides, interviews with activists and recommendations for Black-owned establishments to eat and shop. As you learn about the history of activism in Atlanta, you can order chicken wings at Paschal’s––and sit in the very room where Dr. King and other movement leaders ate and strategized.

Eschewing the deficit-framing and depresencing of sensational coverage, Douglas’ holistic approach grounds these stories in carefully researched detail. The resulting journey of course pays homage to the generations of sacrifice by Black activists fighting systemic racism. But it doesn’t stop at this narrative of struggle and obstacle––rather, it underscores the vibrance of these communities then and now.

“If you flip that deficit frame to an asset frame and say, ‘This place is worthy of engaging with the narrative,’ it makes me wonder––what level of investment follows when you decide the story is good enough?”

Grace Adee